For you always have the poor with you, and you can show kindness to them whenever you wish; but you will not always have me.

I recently had the privilege to sit with Brothers and Sisters from Augustine United Church. We were continuing our work around evangelism in the context of social media. One of the things we wrestled with was moving away from seeing the medium as simply a bulletin board, but more as the commons or town square for an entire generation.

What brought this home was the stat in the socialnomics 2017 video (see below) in which 1 of 3 marriages begin online. Those in the church may find this stat difficult to reconcile with some of their own generational experiences in which the church was the social network, but this online medium is also primarily about relationships, not products or brands. Those certainly flow from the relational reality, but that is not why people are initially engaging.

As with all attempts in which we collect and organise ourselves, there are those who benefit and those do not. There are those who find friends and relationships and those who are isolated and lost. As Jesus' ministry continues to remind us, the poor will always be with us.

- But what does that mean in the twenty-first century?

- What does it mean when one of the central relational spaces for two generations now – Millennials (Gen Y) and Linksters (Gen Z) – is the digital environment?

- What does it mean for a church that does not 'get it,' but is nonetheless directed by a central tenet to share the Good News with the poor?

I am grateful for the work of Johnson Thomaskutty for his multiple-blog series in which he explored the term ‘poor’ used in the Greek (see sidebar): ptōchous. He carefully explores the many ways the word is understood and concludes with the following:

As the Augustinians and I explored the implications of the socialnomics video, we began to discuss the ways in which the digital medium is used for good and ill. As with all technologies, the intention of the person using it is important. Just as importantly, it is not only the intention, but the impact that extends from it. This question is often central for me when I sit with faith communities: why they want to get online?

There are many reasons for this, but one of the clear implications that arises for faith communities is what Christians call 'pastoral care.' If we are entering a medium where everyone is there – from the haves to the have nots – we need to realise we have an opportunity (even an invitation) to offer care, in its range from compassion to solidarity and advocacy.

As I was musing about this week's blog, my experience with Augustine UC and the term "poor," I began to consider that one contemporary metaphor for the poor is the canary in the coal mine. The use of the canary as a bellwether has been historically and literally used to indicate the health of the environment. If the poor, as one way to understood Jesus' challenge, are those who suffer and reflect our culture's inequalities, both figuratively and literally, where are the poor online? What do the canaries in our digital midst have to say to the church's call to help alleviate suffering and oppression in a world bent on fear and division?

The reality and challenge, hope and possibility that became clear to me in this reflection is that the canaries are those who are weaponised and victimised. Whether that is related to gangs, terrorist propaganda, child trafficking and pornography, or bullying online, it is clear where the suffering is happening. The church has a long history of walking into these places of fear and suffering as those who bear light. At the moment, in my context of The United Church of Canada, however, we are just beginning to ask ourselves these pastoral questions as we attempt to shift our own assumptions about social media.

I have shared in these workshops, previously, that if we are not online, our absence simply reinforces a narrative that faith communities are increasingly irrelevant in a secular and humanist context. That challenge – which is both fair and appropriate – belies another question: if we are called to engage in the world, how do we respond if we are not there to offer care? What does it mean to be those who aspire to discipleship, if we are not present to offer kindness (care) to the poor? If we are not doing that, what do we do with the resulting lament that Jesus was right: we will not always have him?

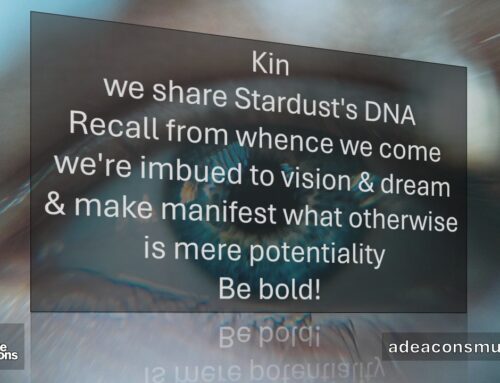

These are neither easy musings, nor do they have simple answers. The potential to share the Good News with those who are marginalized and oppressed, to paraphrase Johnson, is unlimited and ongoing. Social media – as a relational space – simply reminds us of this call. The final question, for this musing then, is how shall we respond?

One of the things that surprised me in ministry was how much pastoral care was done by email and texting. The church must engage with social media to reach out to those beyond the physical walls of the building.

Thanks for taking the time to share this Cindy! I too have found and find that much of my initial pastoral connexions – especially with late Gen X & Millennials begins in social media through DM or PM. Did you find that your ministry preparation helped you or was this a skill set yo uhad to hone? Does that make sense?