Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves.

Prior to exploring Righteous Leadership through the lens of humility, it is important to name the context from which I am writing. I do not assume this is a universal three-part-exploration. It does not purport to set a standard or frame of reference for others for whom the topic is of interest. In my particularity, Righteous Leadership is explored from a context of (white) privilege. This privilege affords me space to learn humility that is different than other Christian kin who might understand such leadership very differently. Such awareness requires me to also recognise that my gender – male – only further affords me privilege.

In the many times in which I have had the honour to walk with others who are living into and/or exploring their discipleship (a Christian parallel to leadership), the tension between ego and confidence has been an important touchstone. In the Psalm passage above, one outcome of leadership that is driven by ego is the temptation of conceit and ambition. What does this mean?

Leadership that devolves into being ego driven can lead to a world view of right/wrong, us/them, you against me. Some call these binaries. They are often influenced by values that lead to seeing those with whom we might disagree as the Other. This conception of otherness, this aspect of ego binaries, ultimately leads to one dehumanising people and de-sanctifying Creation. People become things and nature simply a resource. In the Christian context from which I muse, we would understand this as sin that is experienced as ambition and conceit.

Now some might reply that ego serves a purpose. It might be suggested that, perhaps, it is neutral. It is the choices that we make from a place of ego that are either 'good' or 'bad.' Though I can appreciate this nuance and think it makes for interesting discussion, I do not believe, in the end, that any leadership that is ego-driven serves the person or the community well. Here is why. When we make choices based from the vantage of ego, we are unable to hear we might be wrong, let alone cause hurt or harm to another. Furthermore, ego requires that we hold on to Truth in a way that shapes an individual's and community's identity often in opposition to the Other.

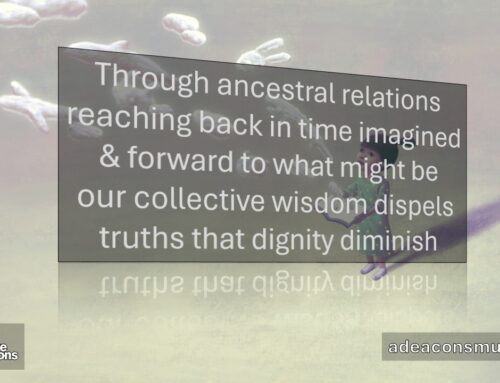

In contrast to ego's need to possess and hold on, confidence is about letting go of truths in the presence of possibility. Confidence makes space to not only be wrong, but also to learn from those moments of stumbling and mistakes. It is this aspect of learning that we will explore more fully in the next addition to this series: Listening and Learning.

This idea of letting go is very old and has an ancient pedigree in regard to the spiritual journey. Letting go of control is a question that Elders and Seers, mystics and ministers not only engage, but ask: whom do you serve? Depending how you answer that question, an exploration of ego and confidence can begin.

From the vantage of leadership, in particular from the Christian context, we are told right from the beginning that our job (or Call) is to care for and steward that which is not ours. As Creator's gardeners, we may be confident in the direction we take and be resilient enough to know we will make mistakes. More importantly, such confidence requires an awareness of the Other. When we awaken, we learn that the Other is simply a mirror of ourselves. What we do to the Other is, ultimately, a reflection of how we care for ourselves as a blessing divine. This revelation, therefore, looks very different if we lead from our ego.

As you consider ego and confidence as aspects of leadership, how do you understand failure? Making mistakes? Answering this honestly, which I admit is not easy, can help all who aspire to righteous leadership to engage in rich, and sometimes difficult, conversation with oneself. More importantly, engaging in such exploration should occur with others, in community. When we recognise our leadership is not isolated from, but intimately wound through, places we call work and play, vocation and career, humility can keep us grounded.

For some, humility might be seen as 'soft' or 'ineffective.' My experience, however, is that humble leadership is resilient and patient. It makes space to see oneself, the Other, and community as an unfolding story, not a punchline or advertising slogan. This takes commitment, and the harvest is the recognition of life's long cycle. In this discipline, ultimately, we often find ourselves not talking at the Other, but sitting with, asking questions, and, when done well, being able to Listen and Learn …

I think you have written admirably about humility. I believe that humility requires a certain amount of gentleness. And a lot of listening. I think it is very hard to lead people when they do not want to go in the direction you are heading.

Blessings, Richard.

Thanks you Rod for this affirmation. Listening and leading are indeed, in my experience, interconnected and require balance beginning with the former: if that makes sense?