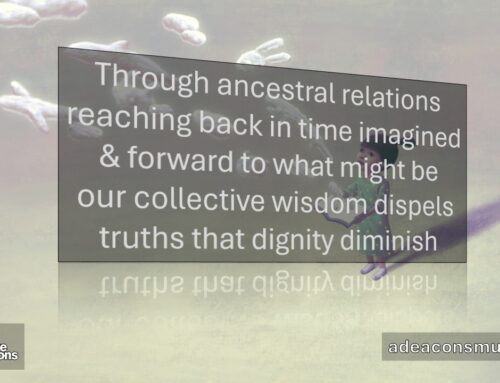

This ten-part A Deacon’s Musing series will explore the intersection between the change philosophy known as Appreciative Inquiry and a Christian theological orientation grounded in diversity. I am most grateful to be co-shaping this conversation with my mentor and friend Maureen McKenna. We sincerely hope that the definitions, metaphors, theological reflections, images, and videos help impart the significant generative potential that is rooted in appreciation, gratitude, and abundance.

As this Appreciative Inquiry series of theological reflections unfold, you can find each blog on the Tabs above.

- Constructionist (170429);

- Simultaneity (170512);

- Anticipatory (170601);

- Poetic (170708); and

- Positive (170721).

- Wholeness (170929);

- Enactment (171020);

- Free Choice (171117);

- Awareness (180209); and

- Narrative (180406).

31 He put before them another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in his field; 32 it is the smallest of all the seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.’

Matthew 13.31-32: Subversion: Weeds, Seeds, & Sowers

Planting seeds – a practice that has an old literal and metaphorical pedigree. It is clear from a context that ranges from the planting of urban flowers and herbs, micro & community gardening to large scale agribusiness, the soil in which we plant, the time to nurture and curate often results in efficient terms like yield, tonnage and bushels. The same can be said of how we plant our words.

When focused or framed upon deficit or that which is lacking, the soil into which seeds are planted does not often bring about the result we wish. This is only exacerbated when we recognise that between us – whether as friends, partners, parents or mentors – we are both the sower and the soil, depending on our context. If, therefore, we wish for harvests that are abundant, both the sower and the seed, the soil and the crop must be recognised to be part of the same ecosystem. What we plant is just as important as how we plant. How we plant is just as important as why we plant. Why we plants is just as important as what we plant: and the circle unfolds …

The literal and metaphorical dance take on an even richer tradition within the Sacred Christian Scriptures. Most of the book of Matthew in Chapter 13 uses metaphors that are seed/sower laden. When taken literally, they can seem to reinforce a sense of privilege and superiority. When removed from the listeners of the day and context of the Rabbi's teachings, it is easy to forget the subversive nature of Jesus' radicalness that positivity – as abundance – is the key to understanding God's Creation. As discussed in the previous exploration of the Poetic Principle, we must always be aware of the layers of meaning which are inherently subversive within the Christian discourse.

If where we focus determines what we see, then how we say it frames what we will hear. Jesus' teaching in Chapter 13 could be heard as a simple sermon that established who is in and who is out. That those who are pure are the good seeds and those that are not, well they're lost. At the beginning of this parable, we might be able to rationalise that. By the time we get to mustard seeds, however, there is word play going on that is radically positive and intrinsically tied to an inclusivity that is about building robust relationships. Ones that reveal ways to be generative in a time and place when the listeners really had no reason to hope.

So let's take a step back …

- This exploration of sower and seed, as metaphor, in the Christian Second Testament begins with Jesus needing a break! But those crowds need and want him, even demand of him;

- Rather than berate, depart or get grumpy, he gets teaching via the use of parable that contained layers and layers of meaning;

- The literal beginning of the teaching makes sense – bad soil, nothing grows; good soil, stuff does;

- Yet … remember a majority of these listeners were not sowers, likely they were the marginalised. They were those who could not afford a dinner out in the suburbs, let alone gardens and especially not owning property to farm;

- And as Jesus nonetheless speaks to them as the 'landed aristocrats, makers of empire, and agrarian poets' he turns everything further topsy-turvy when he gets to mustard seeds …

Mustard seeds? Really? The smallest of grains, yet pretty much a voracious weed. It becomes a tree, suffocating 'good crops.' To add insult to injury, it spreads itself like a rolling stone and attracts birds and creatures who love eating them seeds only to spread them willy-nilly. This – inevitably – in spite of the straight rows we till and plant: think dandelions on steroids!

It's not only crazy, it's his teaching that this is a metaphor for God's world: it's the place Creator longs for us to inhabit! Radically generous and abundance where all live with positive potential that does not divide, but unifies. To get there, we have to begin to let go of assuming we can control the tossing, tilling and subsequent yield potential. For Jesus' listeners, this was a liberating invitation to claim the agency that they were denied by the larger societal realities of the Roman Empire. But … for those who had access to land, planting and the right tools and instruments, it was not such an easy message.

Relationships are hard things, yet when nurtured, like well fertilised soil, they give up new life that sustains all. For this seed-tossing, weed-blooming Kingdom to come, however, all of us have to realise our interdependence. Letting go doesn't mean getting less. It means receiving more of that which is lacking. This can be both exciting and anxious-making as we may not even know, let alone remember, what that might be.

Yet there's Jesus, two millennia ago, telling tales, even though he is exhausted. He's weaving words in a way that is confounding, yet begins to create a path so we can positively and collectively come together and mobilise to do this new thing. It requires cooperation and relationships. But taking those steps, even if you're struggling with letting go or realising you have a voice, points to possibilities unimaginable.

This crazy and radical thing might happen … it's always there beckoning … The question always is: are we willing to risk what our imagination promises or hold tight to what have, even at the expense of the Other?

Well said Richard! Relationships are hard things to nurture. People today are struggling to have a relationship with each other and with the natural world. The mustard see is a great example of a willful plant and one that can plant itself outside of the context in which it was sown. Gardeners know when and where to plant and when to prune and how new plants spring up. Jesus said. I am the Vine and the Father is the gardener (John 15:1). Many people see the gardener as God the Father. However, Psalm 128: 1-3 says “How blessed is everyone who fears the LORD, Who walks in His ways. When you shall eat of the fruit of your hands, You will be happy and it will be well with you. Your wife shall be like a fruitful vine Within your house, Your children like olive plants Around your table.…” It could well be that the Jesus person speaking in this passage of John was the Woman looking for her Lord to father her children. What do you think? Has Patriarchal language and male privilege taken the words of Jesus out of context and allowed them to spread like the seeds of the Mustard tree?

Hi Linda,

What a delightful reply – thank you! I love this word “willful.” It reminds me that in spite of us, the Good News spreads! In particular, this connects with your helpful challenge about the patriarchal framework. I think the egalitarian context of the early Way (Christian Community) and the patriarchal structure as the faith smashed into becoming the religion of the Roman Empire there was planted an intrinsic tension: thoughts?

Yes Richard. Patriarchal language combined with Patriarchal male privilege and the willingness of females to allow male privilege to dominate the public sphere while remaining in the background has led to a Christology that cannot see a female Jesus talking with a male Jesus under the cover of darkness (John 3:1-2). Remember and take note. These two rabbis meet at night. Perhaps, as the Church spread through the Roman Empire with Constantine…people forgot their Greek and forgot how in Greek culture, history is told through stories, fiction and creative non-fiction like the stories recounting the love affair of Pericles and Aspasia. In the John 3 story there are two rabbis. One Rabbi, one Jesus, is the male and the other Rabbi, the other Jesus is the female. The male is the one called Nicodemus. The female one is not named until later in the story. The male Jesus is the one the other unnamed Jesus says is a member of the Jewish Council. The Greek name Nicodemus is a name that advances the plot. It means Victory of the People. It is unfair to blame Constantine for the making of Jesus solely male. Patriarchal language and the notion that Jesus was celibate is also contributing to the dying of the light that believers rage against. Yet…people do love the darkness.

Hi Linda,

Thanks for this – may I say even poetic – response/reflection! What a gift: thank you!

I am not certain I would ‘blame’ Constantine, per se, but our specie’s memory and meaning-making tendency is to forget the community and often to mould the narrative around individuals. Constantine can be considered symbolic of all you have named: does that make sense? I also think that our understanding of the patriarchal culture then and what it actually was has been blurred. I remember in my first graduate programme, after studying Ancient Greek for 6 years, was the first time I dreamed in another language. Sometimes we gloss the past with our today, but I think generally the critique of what we now call patriarchy is ubiquitous and silencing. Though I think there is always temptation to tend to the melancholy, the despondent, the darkness as you have named. the Light always beckons. One of the best Hollywood/pop culture critiques I have seen that tried to express the patriarchy we have and that which was operational for the early church is the movie Agora.

I am not sure I have a point, as much as continuing the conversation with an ellipses …

I agree. One need not blame Constantine or any public leader for our present interpretations of the Bible. Christianity is a religion that requires a mature faith. Patriarchy is not solely to blame either. What I have discovered and am eager to share is the fact that Jesus was and is a threesome that really is a foursome. This fact is not easily understood or explained because of the prevailing belief that Jesus was and is a celibate male. The Agora movie trailer is a good example of how people rise up to defend culture and their vested interests. It makes little difference that a woman is saying come on rally together we are all brothers! Christianity tells the story of how Jesus came to life and dwelled among us. People see the Cross as a cursed tree and see Jesus nailed to this tree that brings death and suffering to all who are nailed to it with him. Jesus was raised from the grave and ascended to heaven after 40 days. This is what they have been taught to see. I’m saying. Whoa back a moment. Let us rethink this story. WHAT IF THE CROSS IS THE FEMALE JESUS who was labelled a sinner woman by the Teacher she anointed and by Simon. How would this change our theology? Would our theology then empower people to step up to the plate and live their lives committed to being in loving relationships face to face with the Truth…owning up to their sins and loving and forgiving one another their offences and trespasses even when the Truth of what they or others have done has hurt others and is exceedingly bitter to face?

As usual Linda, thank you for the reflection and challenge! I had not heard the Cross framed in this manner explicitly. I think that the Gnostic texts (approximately contemporary with the Canon that Church Fathers established) echos some of this implicitly. As well, even in the case of the Greek Patriarchs, the Trinitarian model was poetic and metaphysical in nature, not formulaic and literal. Again, that allows for flexibility that begs us to ask the question: is our interpretative lens ultimately hospitable and compassionate (as in the Way’s first journey) or exclusive and limiting, as occurs in the transition to the State religion that began with the symbol of Constantine. Too dense? Thanks for the great conversation!

Of course you have not heard the Cross framed in this manner. Exegetes and poets/storytellers often are at odds with one another. Exegetes keep things straight and orthodox. if one keeps the story straight and simple…trees can talk with one another and so can rocks…only if the Trees and the Rocks are clued in.

The Trinity is a model and Christians agree the mystery of the Triune is foundational. Academic exegetes have no proof that the story of Jesus is a story crafted to make people work at their spiritual journey. They may suspect that it is. But they treat it as if it were a story written plainly as if for a newspaper.

Surely, I’m not the first to see a tree or a vine as a person. Psalm 128:1-3 says

How blessed is everyone who fears the LORD, Who walks in His ways. 2When you shall eat of the fruit of your hands, You will be happy and it will be well with you. 3Your wife shall be like a fruitful vine Within your house, Your children like olive plants Around your table …and John 15: 1-8 speaks of Jesus being the fruitful vine and the Father being the vine’s husbandman who lops off every branch that does not bear good fruit. Exegetes have made and kept our Trinitarian story a mystery. Keeping the mystery, seems to be the name of the game. In simpler times when people were men or should i say when men were people male and female, people could more easily see the female Jesus speaking with the male Jesus. Check out my blog post about Rudolf the Red nosed Reindeer. http://www.lindavogtturner.ca

Hi Linda,

Again thanks for sharing your reflection. The breadth of the Christian tradition is certainly inspiring and amazing. I am always particularly struck by how our own contextual insights echo with previous parallel spiritual and theological discourses. Once again – thanks for sharing, challenging and engaging in such conversations!

Ditto Richard. Thank you!